Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), commonly referred to as a bone marrow transplant, represents a monumental leap in the treatment of hematologic malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma. For many patients facing aggressive blood cancers or bone marrow failure syndromes, this procedure offers the only potential for a definitive cure. However, the journey does not end with the infusion of new cells. The post-transplant period requires meticulous monitoring to manage potential complications, the most significant of which is an immune condition known as Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD). Leading institutions like Liv Hospital specialize in managing these complex immunological interactions to ensure the best possible outcomes for transplant recipients.

The Biological Mechanism: When the Cure Attacks

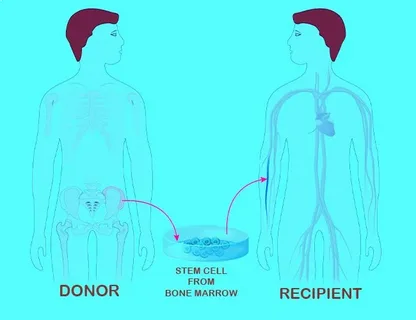

To understand GvHD, one must first distinguish between the two primary types of stem cell transplants: autologous (using the patient’s own cells) and allogeneic (using cells from a donor). GvHD is exclusively a complication of allogeneic transplants. In an allogeneic setting, the patient (the host) receives an immune system from a donor (the graft). Ideally, this new immune system will recognize and destroy any remaining cancer cells—a phenomenon known as the Graft-versus-Tumor (GvT) effect.

However, in cases of Stem Cell Graft versus host, the donor’s T-cells (white blood cells responsible for immune defense) perceive the patient’s healthy tissues as foreign invaders. Instead of just attacking the cancer, these donor cells launch an attack against the host’s body. This biological mismatch can occur even when the donor and recipient are a perfect HLA (Human Leukocyte Antigen) match, as minor histocompatibility antigens can still trigger an immune response.

Acute Graft Versus Host Disease

Classically, GvHD is categorized based on the timing of its onset and its clinical presentation. Acute GvHD typically occurs within the first 100 days following the transplant, though late-onset acute GvHD can occur afterward. It primarily targets three organ systems: the skin, the liver, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

- The Skin: The skin is the most frequently affected organ. Patients often develop a maculopapular rash that may initially resemble a severe sunburn. It commonly starts on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet before spreading to the trunk and extremities. In severe cases, the skin may blister or peel.

- The Liver: When the graft attacks the liver, it causes inflammation and damage to the bile ducts. Clinically, this manifests as jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) and abnormal liver function tests, specifically elevated levels of bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase.

- The Gastrointestinal Tract: GI involvement can be particularly debilitating. Symptoms include severe nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, and high-volume watery diarrhea. Without careful management, this can lead to dehydration and malnutrition.

Medical teams grade acute GvHD on a scale from I (mild) to IV (life-threatening) to determine the aggressiveness of the treatment required.

Chronic Graft Versus Host Disease

Chronic GvHD typically appears after the first 100 days and can persist for months or even years. It is distinct from the acute form not just in timing but in pathophysiology; it behaves more like an autoimmune disorder, such as systemic sclerosis or lupus.

The symptoms of chronic GvHD are more pleiomorphic and can affect nearly every organ system in the body:

- Eyes: Patients often suffer from keratoconjunctivitis sicca, leading to dry, gritty, and painful eyes.

- Mouth: The oral mucosa may develop white, lace-like patches (lichen planus-like changes), sensitivity to spicy foods, and extreme dryness (xerostomia).

- Skin and Joints: The skin may become thickened, tight, and leather-like (sclerodermatous), which can restrict joint mobility and cause contractures.

- Lungs: A serious complication known as bronchiolitis obliterans can occur, causing shortness of breath and chronic non-productive cough due to airway obstruction.

Risk Factors and Prevention

Several factors increase the likelihood of developing GvHD. The degree of HLA mismatch is the most critical predictor; the greater the disparity between donor and recipient antigens, the higher the risk. Other risk factors include the age of the donor and recipient (older age increases risk), the use of peripheral blood stem cells versus bone marrow (peripheral blood has more T-cells), and gender disparity—specifically, a female donor for a male recipient, as the donor cells may react to antigens on the Y chromosome.

Prophylaxis is a standard part of the transplant protocol. Patients are typically placed on immunosuppressive medications, such as calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or cyclosporine) combined with methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil, immediately after the transplant to suppress the donor T-cells’ activity while the new immune system engrafts.

The Delicate Balance of Treatment

Treating GvHD is a balancing act. The goal is to suppress the immune system enough to stop it from damaging healthy organs without suppressing it so much that the patient becomes vulnerable to life-threatening infections or loses the beneficial Graft-versus-Tumor effect. The first-line treatment for both acute and chronic GvHD is usually high-dose systemic corticosteroids.

For patients who do not respond to steroids (steroid-refractory GvHD), second-line therapies are employed. Recent medical advancements have introduced targeted therapies such as ruxolitinib (a JAK inhibitor) and ibrutinib, which have shown promise in modulating the immune response without causing total immune suppression. Extracorporeal Photopheresis (ECP), a procedure where white blood cells are removed, treated with UV light, and returned to the body, is another effective option for skin and visceral involvement in chronic GvHD.

Long-term Outlook and Holistic Recovery

Recovery from a stem cell transplant and the management of GvHD is a marathon, not a sprint. Patients must maintain close contact with their hematology team to monitor for infection and organ function. Nutritional support is vital, particularly for those with GI involvement, as the body requires significant energy to repair tissue damage. Furthermore, physical therapy is often necessary to maintain mobility if skin tightening or muscle weakness occurs.

Beyond the clinical and pharmacological interventions, the psychological and lifestyle aspects of recovery are paramount. Living with a chronic condition requires resilience and a focus on total well-being. Patients are encouraged to engage in gentle physical activity, practice stress-reduction techniques, and maintain a balanced diet to support their immune reconstitution. Embracing a holistic approach to health can significantly improve quality of life during the recovery phase. For those seeking resources on integrating wellness practices into their daily routine, platforms like live and feel offer valuable insights into maintaining a balanced and healthy lifestyle amidst medical challenges.